|

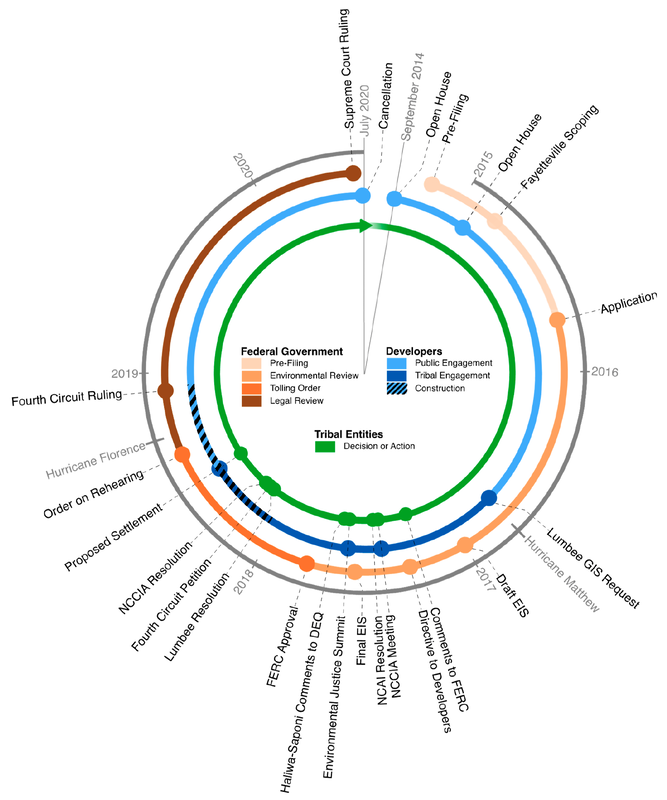

We have a brand new research article in the journal Water on Tribal nations and environmental decision-making. It focuses on state-recognized Tribes and efforts to have their voices heard in planning and permitting for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Check out the graphical timeline below. Read and download the full text here.

In the midst of the COVID pandemic, I pause to celebrate this week’s decision by developers to cancel the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. I stand in solidarity with communities that have been fighting the project for years. Their hard work and optimism are remarkable, and I am convinced that these communities helped tip the scales against a project with powerful corporate and political backing.

The pipeline was intended to transport at least 1.5 billion cubic feet of shale gas daily from fracking operations in Appalachia to endpoints in Virginia and North Carolina. The two energy holding companies developing the pipeline had reserved most of the gas for their affiliated electric utilities, and they had hailed it as critical, job-creating infrastructure. Despite any perceived benefits of the plan, at least two insurmountable problems plagued the Atlantic Coast Pipeline from day one. A new editorial on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline appeared in the NCSU newspaper, The Technician. This piece follows an editorial last week by the Raleigh News and Observer. Both pieces warn that the project may not live up to developers' economic development promises, yet will continue to exacerbate climate change. The developer's advertising campaign continues to focus on potential economic development and possible reduction of greenhouse gas emissions relative to coal.

Here is a Twitter thread that Ryan wrote on Environmental Justice issues at play in Virginia Air Board's review of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline compressor station in Buckingham County, Virginia. You can find the first tweet below. Read the rest of the thread, unrolled, on ThreadReaderApp.

Virginia's Air Board wasn't given page 1 of #environmentaljustice screening reports for proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline industrial site before their Dec. meeting. Read More on ThreadReaderApp... It seemed like Lumbee and other tribal communities in eastern North Carolina had barely recovered from Hurricane Matthew (October 2016) when Hurricane Florence brought even more rain to the region. Lumbee, Coharie, and Waccamaw Siouan people were all impacted seriously by flooding in the wake of Hurricane Florence, which brought more than 30 inches of rain to some parts of eastern North Carolina. Rainfall totals near tribal population centers were closer to 20 inches, which was still enough to cause tremendous flooding

A team led by Mary Finley-Brook (University of Richmond) has new paper in the journal Energy Research & Social Science that takes a critical look at the injustices of "infrastructuring." The authors coin "infrastructuring" to describe the collective processes related to "extracting, storing, transporting, and transforming" fossil fuels. They focus on two projects, a shale gas liquefaction and export facility in Cove Point (MD) and the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a shale gas pipeline expected to cross WV, VA, and NC. The researchers found that each project contributes to multiple categories of injustice. My takeaways from the paper include the following:  This post was originally a thread of Tweets by Ryan. Read the unrolled thread here (includes images). 60 years ago today (January 18, 1958), the Lumbee routed the Ku Klux Klan at the Battle of Hayes Pond. Never heard of the Battle of Hayes Pond? Read on for an amazing, true story. The story comes to me from my parents, who grew up in Robeson County, NC in the 1950s, which is when and where this story takes place. Actually it comes to me from nearly everyone in the Lumbee community old enough to remember. ...this is an epic #Lumbee story, a big deal...  Family gravesite, Saint Annah Church near Prospect, NC. Family gravesite, Saint Annah Church near Prospect, NC.

Throughout 2017, I worked with members of North Carolina's tribal communities to understand what the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline means for indigenous peoples. The people I worked with belong to the Lumbee, Coharie, Haliwa-Saponi, and other tribes. This work merged my service on the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs' Environmental Justice Committee with my growing research interest in the interface between indigenous knowledges and western science. I also interacted with federal, state, and tribal government officials and with corporate leaders representing the pipeline developer. Our discussions covered a wide range of environmental, economic, and cultural issues relating to the pipeline proposal. The journal Science published a summary of my work here. (If you don't have a subscription you can access a PDF here.)

The Fayetteville Observer covered a public meeting in Lumberton on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Although the meeting was nominally about the Department of Environmental Quality's limited role in permitting wetland and stream impacts under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, many attendees spoke out on the pipeline's negative impacts to culture and economy. Because the NC Department of Commerce also attended the meeting, I focused my comments on the negative impacts of climate change, exacerbated by infrastructure like the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. I cited newly published research in Science by Hsiang and colleagues on the uneven distribution of economic damages caused by climate change. I noted that Robeson County would suffer the greatest losses in North Carolina relative to the county's total income. After analyzing publicly available data from Hsiang et al., I noted that NC as a whole would incur damages from climate change totaling billions of dollars annually by the end of this century.

A few weeks ago, I had an opportunity to speak to a large audience on the main stage at Raleigh's March for Science. Afterward, I took some time to reflect on the experience in a blog post for the Global Change Forum at NC State. Click here or on the photo below for a link to the piece I wrote for their blog, Climate Adaptation Planning Stronger with Multiple Ways of Knowing.

Environmental Justice and Tribal Consultation at the North Carolina Indian Unity Conference3/11/2017

Earlier this week, I gave the following address at the opening General Assembly of the 2017 North Carolina Indian Unity Conference. The conference has been held annually since 1976 to bring together leaders and other members of North Carolina's eight recognized tribes. As the Dakota Access Pipeline nears completion, I thought I would post some thoughts here that I have previously shared on FaceBook and other social media sites over the past several months. Back in December 2016, I wrote a FaceBook post about a great infographic created by the New York Times. I updated the post a few weeks later with this text, which has been slightly modified here:

Ryan here. This blog has become stale, but it doesn't mean that my group has been idle. On the contrary, during the past several months, we've been working on a number of research, teaching, and outreach projects of interest to the Native community. Research projects include studying water quality in the Lumbee community after Hurricane Matthew and modeling the impacts of climate and land use change on water in the Lumbee River basin. The former is part of a new collaboration with UNC Chapel Hill and Rosalind Franklin University, and the latter is an ongoing partnership with the US Forest Service. Jocelyn Painter and I presented some of the results from this modeling study at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting last month. I also presented early excerpts of this work during invited seminars in Reston, VA, Pocatello, ID, and Boulder, CO

UNC Chapel Hill student Karine Martel wrote about the Atlantic Coast Pipeline in her environmental journalism course. Her final paper is available here on the UNC American Indian Center's website.

Biwa! (Hello)

My name is Jessica Anstead and I recently received my Bachelors of Science in Secondary Science Education at NC State this spring. Aside from walking across the stage this past semester, I also am excited about the momentous work I have done this year. Many tribal communities in eastern North Carolina are situated near blackwater rivers and pocosin ecosystems. A recent episode of UNC-TV's Exploring North Carolina focuses on these unique natural resources. The video is embedded below and is also available on the UNC-TV website.

Over the past few months, my research group at NC State has been working on a project to combine environmental research with education and outreach among American Indian communities in North Carolina. We are just getting off the ground, but my vision is that this blog will serve as an informal window into our work. Links to scientific research, science news and other scientific resources will appear elsewhere on this site. I hope to use the blog as a tool for placing our own research and other resources found on this website in a culturally relevant context. It may take on other roles, too, as the project evolves.

In the next blog post, one of my undergraduate research assistants (Jocelyn Painter) introduces her project to model the effects of land use and climate change on water resources important to the Lumbee. Her work, which is funded in part by the US Forest Service, aims to connect science and engineering students at NC State with university and Forest Service scientists and the Lumbee community through research and outreach activities. You'll find photos and information about our outreach activities as well as other items of interest on our News page, which is maintained by research assistant Michael Sanderson. Stay tuned for updates about Jocelyn's work and other projects, check back periodically for links to news and other relevant information provided by Michael, and look for us in person at powwows and conferences around the region. Please feel free to visit our Contact page to send feedback and comments. -Ryan Emanuel |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed